berlin fashion week recap

berlin fashion week recap

RECAP OF BERLIN FASHION WEEK: THE HOPEFUL SPARK

Photographer: Isotta Acquati

originally published: 2024/02/14, NuMéRO NETHERLANDS - FASHION

Berlin Fashion Week’s (BFW) four day programme kicked off on the 5th of February, showcasing high quality trailblazing styles under the auspices of the Fashion Council Germany (FCG). With the notable shift in their financial support from sponsorship to that of the Senate, BFW’s core message is one of fearless freedom, responsibility, subcultural creativity, and inclusion. Knowing that the visibility of such fashion is paramount to its international engagement and success, State Secretary Michael Biel (SPD) also spoke of the Senate’s collaboration to conceptually overhaul BFW, starting about one year ago.

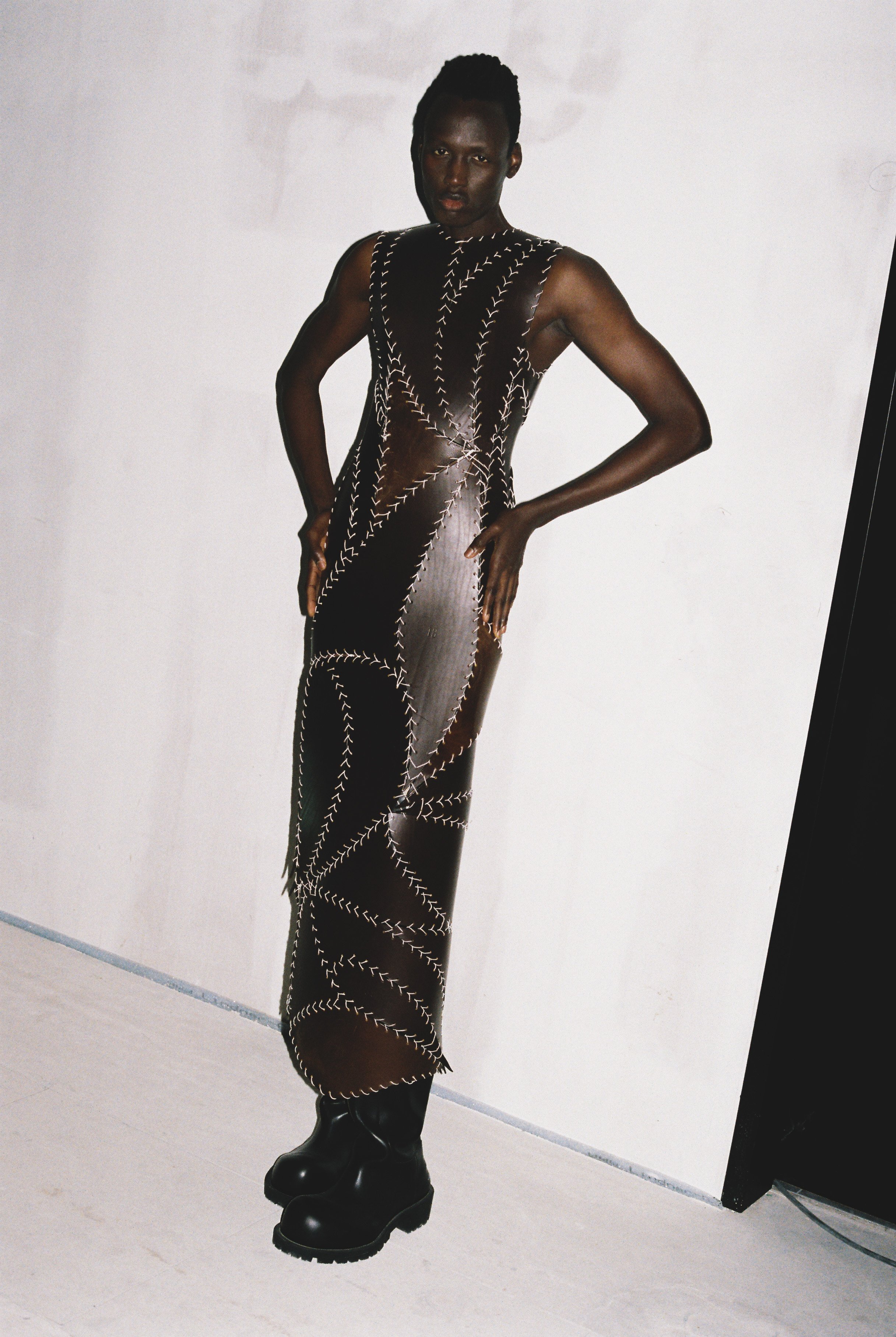

Sia Arnika FW24 collection

As Christiane Arp, COB and founding member of FCG stated at the opening dinner, ‘how we dress will always say something about the world we live in and what is happening around us.’ Biel later added: ‘The local fashion scene reflects Berlin’s unique creativity and freedom like no other, and contributes significantly to the city’s important and international appeal.’

Also announced that night is the fresh initiative: FCG/Vogue Fashion Fund. With only four other countries teaming up with Vogue in this way, having a German counterpart is both a nationwide honour and a boon for Berlin. A jury—consisting of sponsors and illustrious experts such as Edward Enninful, OBE, the Editorial Advisor to British Vogue and Mumi Haiati, CEO and Founder of Reference Studio—will compose a shortlist and choose the winner from these finalists.

Marke FW24 collection

Richert Beil FW24 collection

Another seismic shift in BFW—aside from it now being scheduled so as not to conflict with other industry events—has been the Berlin Contemporary competition. This year saw its third iteration, with 18 designers being awarded 25,000 euros each. Of these winners, seven are brought into focus here. The winners include emergent talents Marke, Sia Arnika, and SF1OG and established designers Lou de Bètoly, Namilia, Richert Beil, and William Fan. Also interviewed are the up-and-coming collective Haderlump, established designer Danny Reinke, and first-time pop-up International Citizen. The following dialogues with and discoveries about these BFW talents prove that Berlin’s fashion scene has peeked out of the darkness, reaching an alluring and promising point.

THE EMERGENTS

HADERLUMP

With notions of collectivity and community at the forefront of their brand, the upcycling focused Haderlump is proud to call Berlin their home. Designer Johann Ehrhardt said, ‘we have plenty of freedom here and can realise ideas that other cities may simply not recognise. Berlin is hard and tender at the same time, both open and closed, slow and fast. Berlin thrives on contradictions, and these are great for exciting fashion.’

Located within this city of harmonious contrasts, this is their third show working as a collective without hierarchy. Using this ‘super contemporary’ work model, they source deadstock materials (i.e. materials deemed worthless) to create high-quality pieces. Their name is admittedly ‘perhaps a little controversial, or let’s say counterintuitive,’ as the term Haderlump recalls rag collectors—those who were usually unhoused using the scraps they found or selling them to paper mills; instead they ‘make clothes out of used material,’ but they ‘liked the industrial…and subversive aspect of the idea.’

Singer Domiziana, wearing Haderlump for the show, expressed her affinity for Berlin—‘some of the coolest people live here and express themselves here’—while also expressing her love for their collaboration; ‘ it feels like something repeatedly iconic that we keep doing.

MARKE

Mario Keine from West Germany, the designer and founder of Marke, had his first full runway show at BFW featuring the second instalment of last season’s cycle, which reflected his ‘design roots.’ Now the ‘reflection cycle’ continues, peering into the question ‘what people shape me during my life?’

The philosophical approach to both his collection and its presentation brings the notion of tabula rasa and talisman to the runway, as models walk along sculptures ‘like silent observers of the past,’ signifying the stages of life. ‘Along your life, you have this collection of talisman you take with you all the time, and which shape you, and the more you live, the more eclectic this collection of talisman gets.’

With sustainability also at the helm of these poetic explorations of the past, all materials are circularly sourced, developed in Cologne, and produced in either Germany or Poland. Of the Berlin scene shifting, he said ‘it’s incredible what turn-around BFW has managed to accomplish,’ and he also expressed his elation that FCG/Vogue Fashion Fund has been announced. ‘Building long-lasting support for young brands,’ he added, ‘we’re on a very good track.’

SF1OG

Designer Rosa Marga Dahl worked with Creative Director Kyra Sophie Wilhemseder for SF1OG’s show this season, and this was the label’s third runway.

Inspired by Dahl’s East German school days while inviting current day contemplation, their collection is also concerned with the past. They created ‘exciting textures through repurposing linen from the 18th and 19th century, leather and other materials,’ all set in a school gymnasium, thereby using a ‘multigenerational perspective’ and inviting the audience to question how the past can commingle with the present through their collection’s creations.

SIA ARNIKA

It’s all about the joy of the journey for Sia Arnika, a Berlin-based Danish designer. Arnika credits the silent era film star Asta Nielsen, a Danish artist who moved to Berlin around 1910, as a major source of inspiration, finding parallels in their journeys despite the centuries that separate them.

Arnika explained, ‘she was also very mundane.’ This seeming contradiction of ‘different kinds of opposing forces’ is what she uses to fuel her collection’s universe of duality. From sound and light, to fabric and shoes— this is a place Arnika is very proud to have meticulously curated, ‘where we have everything working out perfectly.’

While working with a team she trusts, it always came back to her love of the craft: ‘You learn every day, you don’t know where you’ll go, and it is about the journey. I love the textile I have in my hand.’ When asked about creating in a world so filled with chaos, she said: ‘We want to look at beautiful things; you wanna say “good”; you wanna think that you have some sort of community as well—that thing kind of gives you, somehow, power.’ And the power of collaboration in Berlin is not lost on her either. She worked with London and Shanghai based label Untitlab to create shoes, completing the collection’s look and augmenting her brand’s vision.

INTERNATIONAL CITIZEN

Annika Tibando, Vancouver born and NYC established, recently launched International Citizen in Berlin, a place where she believes fashion is ‘going through another emergence.’ Citing her intuition, this she believed was her home for the company.

And it is here, amongst the BFW buzz that her first pop-up occurred, housed in RDV’s permanent Mitte residence until the 17th of February. Not having been in the running for any award (yet?), International Citizen is the result of a ‘personal life pivot’ that landed the ‘universally identifying, sustainable luxury brand’ where it was always ‘destined’ to be.

The label’s ‘DNA is rooted in sustainability through mindful design,’ whereby Tibando ‘weaves energetic modalities like incorporating chakra crystals and colours into minimalistic, cleverly cut, and sensually curious clothing.’ While many of the styles are intended for all genders, ‘the styles are built on the female form.’

Tibando infuses ‘spiritual modalities into the clothing designs and company practice.’ Choosing crystals that will both be hidden or exposed in the clothing, they ‘resonate with the 7-Chakras.’ Sacred geometry such as cubes and prisms are also inspirations for ‘many clothing silhouettes that take their literal form…while the prices of the clothing are considered with the understanding of numerology.’

THE ESTABLISHED

LOU DE BÈTOLY

The eponymous French designer Lou de Bètoly works on one show a year. With artisanship and upcycling at the heart of her Berlin-based label, she started this collection last April, taking her time so she can ‘feel really happy and enjoy the process.’

Among her striking uses of sustainable fabrics, she made a wool skirt suit of dog hair called Chiengora via a German based company. The leather incorporated in this collection was recycled, and she explained, ‘we also made our own fabrics with a weaving loom.’

She works on the mannequin mostly, since the materials are ‘so fragile,’ admitting that this detail and fragility is in itself ‘a weird statement, to do this crazy work on stockings.’ With a mix of time-consuming techniques, such as embroidery and crochet, she adds that ‘the more you go into details, the more you’re like, oh, let’s do it even more fine[ly].’

For her, the realities of BFW mean it cannot aim to compete with major epicentres such as Paris or Milan. Instead, she says, ‘it should have this vibe of new, fresh, ‘cause I think it’s more what it stands for. And there are so many creatives in Berlin that are not even in fashion…I think it would be nice for BFW [to] show this creative scene that is existing already.’

NAMILIA

Namilia is the epitome of BFW subculture; this gender fluid focused brand oozes inclusivity and diversity with their fashion fit for the Berlin club scene.

Founded in 2015 by Nan Li and Emilia Pfohl, ‘the Techno Fashion Label’ once again places worthwhile importance on sex-positivity and body-positivity. This collection is called Pfoten Weg, which Nan Li explained means ‘paws off/don’t touch,’ adding ‘[it’s] like, I wanna hide, but I also wanna be super sexy and provocative.’

The collection uses ‘really strong characters’ to reflect the ‘super diverse and gender fluid’ state of Berlin, where ‘people are coming from everywhere.’ And with these characters, the collection comes to life, highlighting the intersections of self-expression and concomitant concerns about safety in public spaces.

Namilia also reported that while they had been showing in New York the past few years, they’re very pleased to be home in Berlin.

RICHERT BEIL

With a decade under their belt, the duo sought to mark Richert Beil’s ten year anniversary with a reflection of not just their prior collections but also their heritage.

The diverse and inclusive collection is aptly named “Nachlass,”, or Heritage in translation, and it asks some sentimental questions: ‘What is like in a family, what is passed down by your grandmother? What is also passed down by fashion heritage in Germany?’ The word Nachlass elucidates their concept best, but Richert and Beil describe it as what is left after you’ve died, or ‘what’s your footprint?’

Using four elderly women as models—some over 80 years old and mostly from streetcasting—the designers are also concerned with connection. For them, bringing generations together was another pivotal concept not only for the collection and throughout its process, but as larger inspiration.

They wanted to ‘create a world,’ or a ‘surrounding, where all these people exist together, and live in an inclusive world, and make connection points also with each other and see that they might have something in common, or that they can learn from each other.’

Jale Richert went on to explain how taking Berlin as a basis, a place where ‘we have so many different cultures, different types of people, and we can live all together,’ shows why developing an inclusive collection is so important.

WILLIAM FAN

A pillar of the scene, Berlin based label William Fan’s first time at BFW was in 2015. Meanwhile, this is his 18th show, now featuring the “Off Duty” collection: ‘relaxed, casual, like, really chic airport elegance.’ Fan curates such quiet luxury, even down to the sound; ‘it’s my playlist,’ he admits.

Tobias Sagner, who is Hairstylist Lead for the runway show of William Fan, applauded how international their team was and how their 33 models, some of whom were streetcast, were also ‘very diverse.’ He said he really loved the concept of the show, from the ‘very rich fabrics’ to the culture and beauty.

Fan discussed how BFW ‘became smaller, then it became bigger, then [went] back to small again,’ and here we are at this new expanded point. Asserting, ‘it’s healthy to grow slowly and stead[ily] and have…real contact, he went on to recognise how Berlin gave him ‘so much platform’ and feels ‘it’s nice to have [a] real network’ and ‘a lot of support here.’

After expressing how the German and Berlin fashion scene are so important to him, Fan concluded: ‘It feels good that there’s a new generation which is growing up…and so many new people came.’

DANNY REINKE

Founding his label in 2017, Danny Reinke had his first runway with BFW at Mercedes-Benz. With an affinity for artisanship, they ensure ‘every piece of clothing, every detail is carefully handcrafted in the Berlin studio.’ Collaborating with Hannah Kaplan, textile designer, for the first time even allowed for the creation of ‘unique garments refined with gold leaf.’

Reinke explained: ‘As the son of a fisherman, I grew up in a small fishing village on the Stettiner Haff and learned from an early age how important sustainable craftsmanship is.’ Which is why he wants to both ‘preserve and promote it as a fashion label’ that is ‘durable, high quality, and produced to the highest standards: perfectionism throughout—even to the smallest detail.’

He also spoke of how Berlin—far different than the village of his label’s inspirations—still continues to inspire him. As an ‘infinitely diverse city that never stands still,’ he finds ‘this energy is a constant source of inspiration.’ Tracing the constant evolutions through fashion, music, art, and museums, ‘the great cultural offer’ of Berlin ‘influences and shapes’ him.

THE TAKEAWAY

While many of the labels and designers interviewed recognised how much 25,000 euros helped them to realise their concept, even those who were not recipients of the Berlin Contemporary grant this year could see how pivotal it is that BFW is giving access to a larger audience.

Berlin Fashion is about creativity, diversity, inclusivity, and high quality—all while situating itself as a trailblazer. And while the Art scene in this city impacts those who call it home, it is clear that the Fashion is deeply inspired and reflected back to it. Along with last week’s displays of dynamic talent, ingenuity, and fearlessness, the sought after sustainability and international recognition that Berlin Fashion is looking for seem within reach. Indeed, a bright future has been sparked.

Richert Beil FW24 Collection

TEAM CREDITS

Creative Director & Fashion Editor: Charlotte Gindreau

Photographer: Isotta Acquati

Writer: Sandee Woodside

Content Creator: Charlotte Marie Post

read more

the importance of poetry

the importance of poetry

Photo credit: Temporary Truth

originally published: 2018/06/01, The News Lens International — Arts&Culture

Our experience, set in our time in the world, may be shared through any art. We are ready for the pictures of our true life, we are ready for the poems of our true life. All the forms wait for their full language. The poems of the next moment are at hand. – Muriel Rukeyser

Thanks to Instagram, many trends have come to global attention, some of which may not have otherwise done so with the same tenacity. One such phenomenon is the dissemination of poetry – or more specifically, Instapoetry.

The rejuvenated interest in the artform has been of note since the inception of Instapoets in 2015,most notably tied to the popularity of Instagramers Rupi Kapur and Atticus; but their popularity has not come free of contention.

A feverish wrangling, which has descended almost as quickly as the Insta-followers have amassed, surrounds the artistic right to call this breed of poets "Poets." It has been investigated and debated in the mainstream since 2015, from Bustle, The NYT, Rolling Stone, and the Guardian, to blogs of those who sit firmly and unapologetically on either side.

Of these lesser known media-outlets, Soraya Roberts wrote an eloquently vehement piece for American left-wing outlet the Baffler, decrying Instapoetry: “This poetry is not poor because it is genuine, it is poor because that is all it is. To do more than that, regardless of talent, requires time, and, by its very definition, Instapoetry has none.”

However, in the era of the #MeToo movement, and alongside the bigotry rampant in most avenues of social media, the fact that the majority of Instapoetry’s audience is young women makes its dismissal particularly hard to swallow, even by the toughest of critics. "Though critical trepidation is a common consequence of the slippery definition of art … part of this reluctance is also to do with the genre appealing predominantly to young women and haven’t young women been policed enough?” Roberts writes. And as she acknowledges, most Instapoet defenders chant an undeniable chorus: “This poetry speaks to us.”

The one thing we can all manage to agree on is the resurgence of interest in poetry; book sales don’t lie.

The Guardian cites the highest recorded sales ever in 2017 for the UK, and while there is no doubt the arrival of the self-published, young poets spilling short verse into their followers’ feeds has something to do with it, there is also a strong correlation between sales and the emergence of BAME poets – black, Asian, and minority ethnic poets. Voices such as these are breaking the mold, and in doing so are drawing in an audience and readership previously uninterested or disengaged.

Coincidentally, in 2017, the beginnings of another poetic concept were birthed here in Taipei. Taipei Poetry Collective, a poetry group focused on workshopping with other writers based in the city, has been together for a year as of May. So to mark our first anniversary I would like to share our story, as well as remind you of the perpetual importance of poetry.

Poetry and popularity: no longer an unlikely pair

For a long time, poetry has not been mainstream cool. Publications such as Flavorwire or Teen Vogue have been pushing modern poetry on their millennial readers over the last five years or so, but only recently has the trend become apparent.

Nevertheless, the age-old aversion to poetry can likely be traced to two things: the way it has been taught and/or audiences engaging with sub-par poetry.

Poetry should not be inaccessible, nor should it make esoteric demands on the reader; however, many people encounter poetry guarded with the notion they cannot understand – half-formed memories of literary terms and classroom scansion clouds their judgment.

The Academy of American Poets warns against three “false assumptions” the majority of readers will make, thereby stifling their poetic understanding and propensity to engage. Firstly, the assumption that understanding will develop on the first read through, and furthermore, that the reader and/or the poem is to blame if this is not the case. Next, the assumption that via cracking a code the point of the poem will emerge; and by extension, the details in the poem correspond to singular aspects of said code, which must be located and understood. And thirdly, the reader can take the poem to mean whatever he or she wants it to mean.

Of course, engaging with (or “talking to”) the text is a basic analytical skill. But their solution is manifold. You must understand that a creative text is always rooted in context. Next, embrace ambiguity. “The most magical and wonderful poems are ever renewing themselves, which is to say they remain ever mysterious.”

Neophytes might experience verse for the first time outside their classroom days via readings on campuses or in cafes, and perhaps this type of engagement with more amateur poets does more harm than good. Many new poets carry the mistaken notion that in order to write good contemporary poetry, there must be a challenge posed to the reader. The uninitiated poetry audience may latch onto any moments of confusion as a further impetus to steer clear of the form, and back to their prose they go.

On the opposite end of this spectrum lies the current debate on whether Instapoets and their ilk should be given the title of poet at all; the seemingly cliché verses do taper into the mundane and obvious, and therefore fail to tick off the stylistic markers of the “literary.” These debates aside, what is most important is that world renowned poets and teachers have been working to dismantle the idea that good poetry must not be indecipherable either.

In an opinion piece for the NYT, award-winning poet American Matthew Zapruder explains, “I don’t know what writers of stories, novels and essays eventually discover for themselves, but I can say that sooner or later poets figure out that there are no new ideas, only the same old ones – and that nobody who loves poetry reads it to be impressed, but to experience and feel and understand in ways only poetry can conjure.”

As another award-winning American poet, Jane Hirshfield has said, “a poem is a set of words that simply have a higher meaning to moment ratio than other words do.” Upon hearing this rather simple sentiment in a BBC podcast, I felt uncannily elated. It is exactly this power and the lasting endurance of the words in verse that propel multifarious meanings, allowing us to connect across and against time and space.

In a similar vein, “The Life of Poetry” by the highly influential and groundbreaking 20th century American poet Muriel Rukeyser, whose quote I open this piece with, puts it rather bluntly: "Poetry has often failed us. It has, often, not been good enough [...] It is necessary that the 25th century know that we wrote trash. It is necessary that enough be done by then so that we all be seen resisting things which have for them changed and fallen away – transitional. Our poems will have failed if our readers are not brought by them beyond the poems."

And so we must accept a poem will never be entirely new nor concrete; yet it is inherently born anew in each instance, and it’s just as capable of transporting its reader in each interaction.

With these intricately balanced (and at times epic) aims in mind – to better our writing, to probe if our ideas are emotive and clear, to engage with other poets’ styles and experiences, and to scrutinize in a constructive manner their endurance – especially as anglophone writers, most of us far away from home and feedback – Taipei Poetry Collective came to fruition.

The fact there has been a poetic renaissance as of late is merely incidental. But hey, it’s nice to know we’re not alone – even if there is a culture war raging on.

Personally, creating any type of art devoid of aspirations to success is paramount; it’s all part of the individualized process of self-expression and creative critical engagement with our surroundings. With that said, most desire their coveted artistic form of expression to be appreciated and valued, and finally here we now sit. Pens ready, 7-11 print-outs in hand.

The collective’s beginnings

Having first met in late 2016, Alexandra Gilliam, Ashley Jade and I began speaking about our poetic passions at the artistic community space Red Room. After tossing some ideas around in passing, we finally sat down together in April of last year. This was the starting point of what would become TPC today, and it’s humbling to see how much has transpired, the progress we’ve made, and how many connections we’ve forged in the past year.

We now have over 150 members, had three readings, and self-published two zines of featured poetry – and that’s aside from our biweekly workshops, alternating weekday and Sunday nights to ensure accessibility.

Alexandra recalls that Ashley had an idea for a workshop and I had experience with running poetry readings. Noting these strengths – and coupling them with her own graduate school experiences, which have helped her “better prepare for the wild, unexpected, crazy, magic understanding that can happen in a workshop environment” – collaboration was obviously the next step.

Experienced in editing literary journals, Alexandra’s previous process of critiquing poetry has been essential to not only our workshop participants, but also our selection process during our event/zine curations. Having received her MFA in Creative Writing from California College of the Arts, it was here she actualized her passion for contemporary poetry. She is the author of chapbook “Femmestuary” (dancing girl press, 2016), in which you can find sparse but highly imagistic form tackling both the political and the personal with an almost paradoxical ephemeral gravity.

During her teacher’s assistantship in her grad program she was also the editor for the school’s undergraduate literary journal. As such, Alexandra has reams of experience in editing and preparing submissions for students, as well as design layout for the online and print journal.

For Ashley, the starting point is traced back to the open mic format, but she notes, they “only go so far in terms of developing us as poets. We all agreed we wanted a domain specifically for poetry here in Taipei.”

In 2013, while studying English Literature in the State University of New York, Ashley started an open mic night and online lit magazine. “It was short-lived, but was a start,” she recounts, as she was set to relocate to Taiwan. Known for her 10-liner poems, literally ripe with heaving imagery, her more recent work has transitioned from her Taiwan experiences into the cosmos, where she tempts feelings of progress and transformation. Her “general love for humans and the desire to be a part of and a driving force in community” have bolstered her abilities to co-run our workshops and events.

Joining our ranks from the start, we were lucky enough to have Leora Joy Jones. She is a published writer and a practicing artist, with a background in Fine Arts. She now serves as a co-founder in TPC after our first Versify event last November. Preferring straightforward language, Leora probes at the intersections between everyday life and popular culture.

Her poetry demands simultaneous emotions from her audience – in magnifying the more mundane portions of communication and interaction with interspersed trauma, she breaks through spheres of privacy, calling into question our own innocence. Not only does she write poetry, Leora also makes analog collages – preferring this medium as it is more mobile, and can be made anywhere.

As for myself, I was a writing consultant for the The City College of New York’s Writing Center, which served as my cornerstone in constructive criticism and editing. While studying for my BA in Literature, my poetry took root as well. I was published in my alma mater’s literary journal, and was subsequently up for the editor position at the journal. I was unable to take it, as my plans to leave for Vietnam were contingent upon a position opening there.

Missing this opportunity was a sore spot, and as such my poetic output was back-burnered after my relocation. It wasn’t until 2015 that I began performing again in Saigon, culminating in my curation of a mixed media literary event just a week before coming to Taipei. With this freshly stoked passion in tow, I arrived seeking a community for my poetry – initially at Red Room, where I was lucky enough to find Ashley and Alex.

Thanks to their guidance, my first chapbook “devise(h)er” is forthcoming with dancing girl press later this year. My poetry has been described by Leora as “dense and lyrical, thickened with reckonings of the past and future imaginings, highly visual and visceral.” For Alex, “[it] contemplates existence, myth, and rebirth using a sweeping poetic narrative that shows us the depth of our identity. It’s alive, breathing, metaphysical as we decipher the real from our perceptions.”

Each of us have extremely different styles. From the way we write or deliver our poetry, to the manner in which we edit, plan, and advise, we couldn’t be more distinct. Yet all of us prioritize poetry in our lives while fostering this importance in others. Moreover, we each aim to stimulate the artistic community at large through our collective’s verse.

The relevance of poetry

When discussing the importance of poetry, as well as what challenges we have faced in being poets in Taipei and to what extent TPC has mollified those changes, all four of us agreed the sense of expression and issues of isolation were pivotal.

Dismissing the idea that poetry’s private and subjective nature should be a hindrance, Leora makes it known that it all can be shared: “It could be raw, but with attention and thoughtful editing, the private can be made public. So it’s special to have a group of people you can get vulnerable with, and workshopping emotions and feelings seems counterintuitive, but it works. I’ve seen so much growth in my own writing from the constant biweekly framework.”

These workshops truly are the heart of TPC.

For me, back in Saigon I was frequently the only poet performing at events. Without critical engagement, I felt isolated as well as stagnant. Unfortunately, the promise of a larger anglophone demographic here in Taipei also did not fill the void. But what finally has is the community we’ve managed to help foster here. The insights and challenges presented over the past year’s workshopping have been, for me, unmatched.

Alex recounts a similar unfolding. “When I left for Taipei, my mentor warned me to not isolate myself,” but that wasn’t always easy.“ I feel a sense of guilt in not being able to speak Mandarin because it keeps me at a distance from the local community and culture. That being said, we really rely on our close knit community for everything. TPC has been my foundation to reconnect and critique my poetry/my art.”

And through the more polished poetic realizations we communally encounter during those hours together, we create art and challenge one another with the hopes of inviting feelings. And with our readings and zines, these feelings can now be shared every few months with you, as well.

On April 21, we had our most recent reading event, Versify II. Coming off this buzz, the four of us are already planning our next moves, discussing collaborative projects and methods to make our passion more accessible. For one, our latest zine is now available at Ivy Palace, URBN Culture, Oomph and Red Room, literally spreading poetry across the city in the hopes that more time spent engaging with the words we’ve curated can help build broader understanding and appreciation. Couple that with the thoughts on reading poetry herein, and engaging with our chosen art form is now even more attainable.

We also discussed ways to mitigate the implicit social and language barriers. To this end, the weekend of June 2-3, we will be at the ACID EFKT arts and crafts festival. But don’t come expecting any poetry from us. Instead we’ll have our first alternative-style workshop; geared towards English language learners as well as anglophones, we will be creating poems communally in the hopes of extending our passion. Our mission is to engage, inspire, and reach out to this magnetic city in order to foster experimentation with English language verse. As Ashley puts it, “while I'm sure there is a world of poetry here in Mandarin, unfortunately there isn't much crossover; TPC is the start of a community, and a chance for us all to continue growing.”

TNL Editor: David Green

read more

shame, pleasure and affirmative consent

shame, pleasure and affirmative consent

Shame, Pleasure and Affirmative Consent

Credit: Reuters / TPG

originally published: 2018/10/11, The New Lens International – Society

Speaking up about sexual assault amidst the patriarchal structures we are entrenched in has shown itself to be inconsequential. Also irrelevant were the psychiatrists and neuroscientists vouching for the validity of not wanting to come forward and yet having such vivid memories of the traumatic event – for a lifetime. Of course, I am speaking of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

As nefarious as the results of the U.S. Senate hearing and Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry may seem to most people, the greatest evil is the attempt to placate the global audience with promises of justice being served through not “ruining a good man’s name” – to paraphrase Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s chief defender, the Republican Senator Lindsey Graham.

Heaven forbid we ruin a good man’s name.

But let’s stop and think for a moment: Who, now that Kavanaugh has been seated, will feel the ramifications? The women. The victims. Those brave enough to stand up against the system. They will be ruined.

For the survivors of assault, there is no such thing as erasure. Whether they confront or not, the slate will never come fully clean, and the best they can hope for is a higher ratio of acknowledgment of their pain than cynicism from those who protect the assailants.

Please keep this in mind as we move from the outrage that has unfolded in the U.S. and focus on the manifestations of these deep seated issues here in Taipei.

***

Having sat down in a small dark room, I adjusted my position to better keep an eye on the man in front of me as he maniacally leapt from one dingy hotel twin bed to the other. A knot began to form in my throat. I was to remain silent for the next 75 minutes despite numerous urges to shout or gasp – but there was no intermission in this production of “Tape.”

The spectrum of emotions and the intensities of memories each audience member experienced will remain undisclosed. For some, however, this dramatization acted as a catalyst; people in Taipei have started talking a lot about rape.

There are numerous resources for meaningful discussion (such as this and this), which do not situate all masculinity as pure evil, but instead deconstruct its insidious influence throughout societies, and those should be explored.

For a more radical discussion of masculinity as a construct – written by men – this interview is worth your time. And in light of the recent developments regarding the #MeToo movement let us not forget, “It is far easier to assign blame to the broad category of men than it is to reckon with the myriad ways power manifests itself in the structures that connect human beings to one another.” This is not merely about gender or gender roles; this is about our patriarchal societies, false entitlement, and misdirected shame.

Instead of rooting this exploration in toxicity and power, I propose looking toward pleasure for an answer. I have come to regard consent, shame, and pleasure as inextricably linked, though infrequently mandated as such.

Those who feel entitled to their own needs and pleasure without having a firm grasp on their counterpart’s considerations promulgate systemic evil. Consent is not clearly understood because our fundamental understanding of a pleasure devoid of entitlement and power has not been taught or explored.

This is not merely about gender or gender roles; this is about our patriarchal societies, false entitlement, and misdirected shame.

Anchoring this consideration and approach to conversations already underway here, I was lucky enough to talk with Michelle Kao, the actress in the recent production of the drama “Tape” held at the Butterfly Effect theater. I have also interviewed Bianca Lin, who was the Administrative Director of the theater.

Other voices came forward, too; this time for much less fortunate reasons. There was a recent rape within the foreigner community here in Taipei. I know both parties involved, and the victim has given me permission to incorporate her public statement.

By exploring the plot line and characterizations in “Tape” to the dialogue taking place in real time here in Taipei, the inadequacies of our understanding burst through the seams of the discussions we are enabling.

To respect the privacy of some parties involved, some names have been omitted.

Understanding shame

Before we enter into discussion of victim blaming, or the dismissal of shame that victims (and even perpetrators) may feel, we need to investigate where this shame comes from. We need to better understand that shame itself is a product of the very institutions and structures espousing patriarchy, restricting dissenting voices, or silencing these trauma narratives all together.

Mr. Klein, a psychotherapist writing for The New York Times, explains in his opinion piece ‘What Men Say About #MeToo in Therapy’: “Shame is the emotional weapon that allows patriarchal behaviors to flourish. The fear of being emasculated leads men to rationalize awful behavior. This kind of toxic shame is in direct contradiction with the healthy shame that we all need to feel in order to acknowledge mistakes and take responsibility.”

Most importantly, the shame must be laid at the feet of the abusers – not the survivors.

So shame – as an innate emotion – is not a bad thing. From feeling shame simply because of being a man or being ashamed of past actions which would be considered assault, to feeling shame because you’re a survivor of assault or being ashamed to admit your loss of agency in such situations, this is not a cut and dry emotional response.

Yet any healthy version of it would indicate internal change. So though shame itself is perfectly natural, a line between humility and humiliation must be societally acknowledged in order to make space for redemption. And most importantly, the shame must be laid at the feet of the abusers – not the survivors.

For Kao, the issues surrounding this sense of shame relate to victims first: “I think shame plays a huge part in not feeling like you can reach out for support or justice after something like sexual assault has happened. Whether it is a product of social stigma or culturally, women tend to blame themselves first, even if they are clearly a victim. It’s easy to be blinded by shame and not see the fact that something out of your control is wrong.”

Kao was fortunate enough to have spoken up during an incident in her teenage years. When she acted upon her discomfort after a male camp counselor made sexual comments to her, she was assured “even just passing comments...was considered a form of sexual harassment.” She had every right to speak up and there were ramifications for his actions. “In the past, when I got sexually harassed on public transport, I just got angry inside but wasn’t brave enough to say or do anything. This is why I think education or conversation early on in adolescence would have been hugely helpful.”

For Bianca Lin, many issues in Taiwan have to do with the fact “education (from family and the society) is still dominated by men’s point of view.” Despite patriarchal views opposing empowering efforts, “we are trying really hard to educate young girls that they have their own right[s over] their own bodies.”

When asked what they would say is the opposite of shame, both Kao and Lin cited being “comfortable,” while Kao took it a step further to say feeling “supported” as well. This comfort and support should come from our partners, yes. But it also needs to stem from society.

Permission and pleasure

If we don’t discuss what sex should be – directive, communicative, pleasurable explorations of others’ desires – how can we expect to destroy the structures in place protecting perpetrators, shaming victims, blaming accusers, and confusing all of those on this spectrum? How can we instill the importance of consent, if we don’t discuss what we are giving permission for?

I’m not alone in proposing this type of education as an antithesis to the confusion sadly still circulating around consent. Using the benchmark of: “1. Do I feel safe saying no? 2. Is my pleasure as important as his? 3. Does the sex end when he does?”, Andrea Barrica wrote an article for The Establishment earlier this year embracing a similar argument. Consent cannot be discussed without pleasure being understood.

In Taiwan, this is where the ‘Only Yes Means Yes’ campaign comes in. This affirmative consent campaign, reportedly based on foreign models, is taught through the Modern Women’s Foundation (MWF), which has been working towards gender safety and equality in various guises since 1987.

Kao explained: “In Taiwan, when cases are reported or are in court, so much emphasis was placed on ‘well, did you actually say no?’ Most time and energy was focused on hashing out details and figuring out what constituted ‘No.’ The goal of the ‘Only Yes Means Yes’ campaign is to shift the focus of investigation and interrogation, to where only ‘Yes’ means consent. So in consensual sex, there needs to be a clear invitation to have sex by one side, and a clear ‘Yes’ of consent from the other side.”

Lin added: “It’s too much in the culture if you don’t say anything, people just assume you agreed to something you don’t want to do…[and while] victims might have some physical reaction...it’s just a normal response, [but] doesn’t mean it’s consent.”

Another affirmative taking the internet – and bedrooms – by storm is OMGYes. Emma Watson praises it, a thousand women have contributed to it, and serious research supports it. The subscription based website not only educates women about their own bodies and the possibilities of their pleasure using language hitherto unavailable, but even men have had their expectations exceeded when it comes to educational and practical information. So perhaps in a place like Taiwan, where revolutionary sex education in the classroom is a far off concept, the privacy and discretion OMGYes can offer could very well be the way forward. (And yes, it’s currently available in 12 languages, included Traditional Chinese).

Kao answered with a resounding “YES” when I asked her if she agrees education about consent should come with education about pleasure; as did Bianca – but with less capitalization. For Kao, however, the question prompted memories of fear, which she felt would have been lessened if education like that had been the norm, along with some retrospective but unpleasant recollections. “Wow, I’m just remembering again, the bruises. He didn’t know what he was doing either, and I didn’t know better.”

#MeToo and the manifestations in Taipei

Amid allegations against known feminists – from a #MeToo figurehead, Asia Argento, to academics and a UN official, Avital Ronell, Michael Kimmel, and Ravi Karkara – concern about discrediting a movement meant to reveal and destroy the power structures and systemic abuse latent in such hierarchies is mounting.

As I was in the midst of reading through articles exploring the nature of support and its denial for some of these aforementioned feminists, a friend alerted me to the recent rape in Taipei. There will be no officials involved. No one will be entered into an ever growing database of allegations. And yet, a statement was made. The victim came forward on her social media to explain the assault and name the accused. (Later, the perpetrator also came forward to attempt a public apology on his own social media.)

Because the woman who was assaulted was still unsure if she was going public, I was informed of the situation before I knew who the victim was. I had worked closely with the accused. I had a meeting with him in a few hours, which I was hoping he wouldn’t have the audacity to show up to. I had many more questions than I had answers, but I was certain my foundation had been rattled.

A cognitive dissonance occurred; I was being forced to compartmentalize during my interaction with him, and the only way I made it through without addressing the issue head-on was by reminding myself how many perpetrators are being conversed with every minute, unknowingly. At least because of that victim’s bravery, I was aware. Out of respect for her voice, I held my tongue.

This brings us back to the play, “Tape.” If you are unaware of the plot, here’s a quick summation: Two best friends since childhood, Vince and Jon, reunite, only to have Vince exact his plan to audio-record Jon admitting to having raped Vince’s ex-girlfriend, Amy, back in high school. Soon Amy arrives on the scene, and the trio’s strained conversations oscillate between skirting around and tackling head on the issues of consent, shame, and redemption – the seething storyline forcing the audience to remain uncomfortably on edge the entire time. In the end, Amy chooses to reclaim some power by misleading the men to think police are on the way. Jon sits still – awaiting the justice he now realizes he deserves. In the end, it is revealed Amy only feigned making the call, but lessons have surely begun to take root.

The play highlights not only the denial perpetrators may face, as what is seen as “rough” to one is certainly non-consensual to the other, it also brings to light the interplay of shame: from Amy’s inability to admit it was rape for all these years – amid hints at the damage it had done to her body image, to Jon’s ultimate acceptance of his criminality and shame. Lastly, and especially relevant, is the victim’s choice to not report the crime to the authorities, but to instead invoke her own authority in order to deal with the crime via conversation and communal acknowledgment.

Michelle Kao, who played Amy, commented: “I have thankfully never been sexually assaulted. But from my past experiences with PTSD (in relation to suicide), calorie counting in college, being cheated on, and having a very rocky introduction to sex and intimacy, I can imagine just how destroyed Amy, in ‘Tape,’ would be after being date raped by someone she really cared for and trusted. The road to recovering a sense of self worth and purpose is long and difficult. Being betrayed both physically and emotionally is detrimental to having a healthy body image, and when you feel ashamed and can’t talk about the trauma, it’s easy to turn to an eating disorder.”

Grappling with how to feel about Jon’s character was more complicated. Should we feel relief that he sat waiting for the authorities? Are we right in feeling disappointed that justice wasn’t served? The only certainty is that it’s up to the victim how to deal with exacting punishment for the assault – but this was a fiction, meant to spark conversation about our own sympathies.

As far as we – the audience, the readership, the periphery, or even the friends – should react in real life situations, I draw a thick line.

I witnessed a woman (and a friend) get up to bat for the perpetrator; she even helped him draft his two week late public apology. She reasoned that his version of the evening was very different from the victim’s, and he therefore needed guidance in order to learn and grow. Despite all logical arguments I could muster, her defense remained. Not that he didn’t do it. Not that he didn’t deserve to be called out on it, even. But that we – as women, as victims ourselves of the systemic abuse – owe it to him and all perpetrators to help.

Coddling abusers in their path to healing is fundamentally patriarchal.

To this I scream: No we do not! And as recently, via a Vox article, I now have the validation of a male screaming it along with me. (So, you know, maybe the sentiment will be taken seriously and the “demographics that may be reachable by a dudely voice that are not being reached by female voices” can be tapped into.) In David Roberts’ words: “Talking about the perpetrators ‘moving on with their lives’ at all, much less with sympathy and solicitude, is a clear signal that the moral weight and severity of the crisis has not sunk in. We’re still not taking this shit seriously.”

Coddling abusers in their path to healing is fundamentally patriarchal. It has been ingrained in us, sure; that makes it lazy, not logical. It requires no emotional response and no advocacy beyond a pat on the well-worn back of the shamed perpetrator.

The online community’s ardent support for the victim here in Taipei – despite the assaulter’s acceptance of responsibility and wrongdoing – seemed for some uncalled for. If he’s admitting to it, shouldn’t we stop trolling him? I didn't mince words: We should not be applauding people who sexually assault other people for agreeing that they have sexually assaulted someone, and we certainly shouldn’t be applauding them for doing so after they have had to have it spelled out to them, pushed to offer an actual apology.

We should not be applauding people who sexually assault other people for agreeing that they have sexually assaulted someone.

At the same time, a witch hunt is not what the victim wanted, and for those reasons we should act only for our own hurt, not in the name of someone else’s. In her words: “I would like to make it clear that my goal here is to encourage conversation, not to trigger a witch hunt, campaign of hate, or any sort of violent reprisal.”

It is up to each individual how they choose to express their disapproval, allyship, and/or solidarity. There is no one right way. There are, however, quite a few damaging and backward paths one could choose. Acknowledging the truth in an accusation does nothing in isolation, especially when this abuser was an ally. In the woman’s words: “He is a respected artist in the community, someone who makes things happen, someone who empowers the people he sees potential in.”

He is a supporter of the #MeToo movement and of feminism in general. I mention this because even people who represent themselves as allies are capable of this evil. It is good we are having more conversations about rape and consent but obviously there is still much to do.” And yes, there are steps that can be taken even for delusions as deep as this.

Also in the realm of counterproductive responses were discussions that went a bit like this: "Well, it’s not really rape – shouldn’t we find another word for it?" And, to be clear, I’m not above any of this. I was raped years ago, and have only recently been able to call it what it was. In fact, I was assaulted more than once, and the impending shame of discussing it or even naming it kept me from saying anything.

During these conversations, women recalled situations in which things were hazy, consent wasn’t given, “but nothing violent happened.” They gave in, so they say it wasn’t rape-rape. They wondered about over-using the term. They felt it should be reserved for that small percentage of women so brutally attacked that they do become a statistic and a newsreel presence.

It is in the more sweeping definition that so many people will find themselves sitting – 81 percent of women, in fact. But no one ever asks to be a victim, which is why conversations have shifted to refer to these women (and men, as the term applies to all those assaulted) as survivors. Victim or survivor, the fact remains that unless we call the crime what it is – that uncomfortable word rape – then we do not have a chance in hell to stop the abuse. The word has more power than these perpetrators will ever have. We must use it.

In the words of the victim discussed herein, “Our voices can become weapons of dissuasion and tools of empowerment.” The first step then is to name it.

The word 'rape' has more power than these perpetrators will ever have. We must use it.

It is a shameful word not because victims should be ashamed, but because the power wielding, entitled, aggressors should be. And just because a handful of them are, in retrospect, self-aware enough to admit their criminality, this in no way indicates the issue is resolved.

Also from the woman’s post: “Of course, it is for the victims of assault to choose for themselves whether to speak out or not, according to what they think is better for them...but the ones who speak up shouldn't be the ones left to live in shame, guilt, and fear. The perpetrators and the ones who protect them are the ones who should be carrying this burden.”

And with this burden, what will help is open conversation, professional therapy, uncomfortable knowledge, more frank discussion, and ever expanding awareness.

In both the fictionalized drama “Tape” and the virtual discussion in Taipei, the shame shifted from victim to perpetrator. Yet, was that going to happen with or without his admission and apology? And will this always be the case? Depending on where someone is located and the support he or she has, probably not.

While these narratives and reactions are surfacing, simultaneously we must be shifting conversations and education to pleasure.

Therefore, the doubt when these questions are asked needs to be obliterated. It is only due to the multilayered nature of sexual abuse and abuse of power that we even have to stop and think about this. And it’s going to take a lot more discussion to reach the point at which the knee-jerk reaction has nothing to do with gender or sexuality, has nothing to do with geographical location or the time of day, the outfit worn or the blood alcohol content, but does have to do with a victim using immense bravery and power despite the trauma to use his or her voice.

While these narratives and reactions are surfacing, simultaneously we must be shifting conversations and education to pleasure. The fact that a #MeToo supporter was allegedly unable to understand what consent really looked like, although he has read up and commented on the issue, points to the reality of consent not being taught (if not something much more sinister). Consent is so much more than the nod of the head – and it is certainly not when the shake of a head finally stops. It is a dialogue. And it must be expounded as such.

The affirmative action ‘Only Yes means Yes’ campaign is certainly a starting point. Perhaps more discreet educational programs, like OMGYes or small workshops offered at places like MOWES can also help fill a void, especially in a culture where sexual education is not up to the task. Kao explains, as a teacher here in Taipei: “The #MeToo movement in itself of course encourages conversation. But I have also found that just the being able to reference the phrase ‘#MeToo,’ instead of saying rape or date rape, make it easier for me to talk about the issue with students and male colleagues.”

And hopefully, in time, more discussions will be had and progress will be made. But in both the play and the rape‚ there were foreigners involved: foreigners who are typically better versed in these topics or more exposed to discussions of this nature.

The people I spoke to – mostly friends and some women, artists, feminists – appalled me again and again throughout my conversations. Lazy thinking and easy resolutions, especially while living in a patriarchal and traditional society such as this one, are nearly as malignant as those who commit the crimes.

Whether through the use of physical art or virtual spaces, we must grow in our support of these conversations. We must keep reading and asking and listening. We must learn how to helpfully respond to victims who come forward. We must stop pandering to abusers because we’re used to doing so, and that makes it easier than standing up for those around us. We can surmount the barriers around these treacherously enabling perspectives and destroy these damaging monologues – foreigner or local, here or abroad, feminist or not.

TNL Editor: David Green

read more

saying OK aloud to:

saying OK aloud to:

saying OK aloud to:

Photo Credit: Cathy Keng

originally published: 2022/06/18 - Taipei Poetry Collective Versify III zine

found after mints & other consolationos

found after mints & other consolationos

found after dinner mints & other consolations

Photo Credit: Cathy Keng

originally published: 2022/06/18 - Taipei Poetry Collective Versify III zine

metadiscourses

metadiscourses

metadiscourses

Photo Credit: Chao Abby

originally published: 2018/04/21 - Taipei Poetry Collective Versify II zine

woman

woman

woman

originally published: 2017/11/25 - Taipei Poetry Collective Versify zine

skinscapes

skinscapes

of all the skinscapes, yours is the most unavoidable

originally published: 2017/11/25 - Taipei Poetry Collective Versify zine

positioned

positioned

positioned as first thing i see when i wake up:

Photo Credit: Temporary Truth

read more